David H. Pinkney, Napoleon III and the rebuilding of Paris (1)

A Positive Overview of Haussmanization

"I WANT TO BE A SECOND AUGUSTUS," wrote Louis Napoleon Bonaparte in 1842 from his prison in the fortress of Ham, "because Augustus... made Rome a city of marble."' This nephew of the Emperor Napoleon, sentenced to life imprisonment for an attempt to overthrow the monarchy two years earlier, was hoping to revive the Empire, and he was also dreaming of rebuilding Paris as a city of marble befitting the new imperial France. In 1846 he escaped from prison, and in 1848 he returned to Paris to become the President of the Second Republic. A few years later he did restore the Empire, styling himself Napoleon III, and in the two decades after 1850 he rebuilt much of Paris.

Ham, "because Augustus... made Rome a city of marble."' This nephew of the Emperor Napoleon, sentenced to life imprisonment for an attempt to overthrow the monarchy two years earlier, was hoping to revive the Empire, and he was also dreaming of rebuilding Paris as a city of marble befitting the new imperial France. In 1846 he escaped from prison, and in 1848 he returned to Paris to become the President of the Second Republic. A few years later he did restore the Empire, styling himself Napoleon III, and in the two decades after 1850 he rebuilt much of Paris.

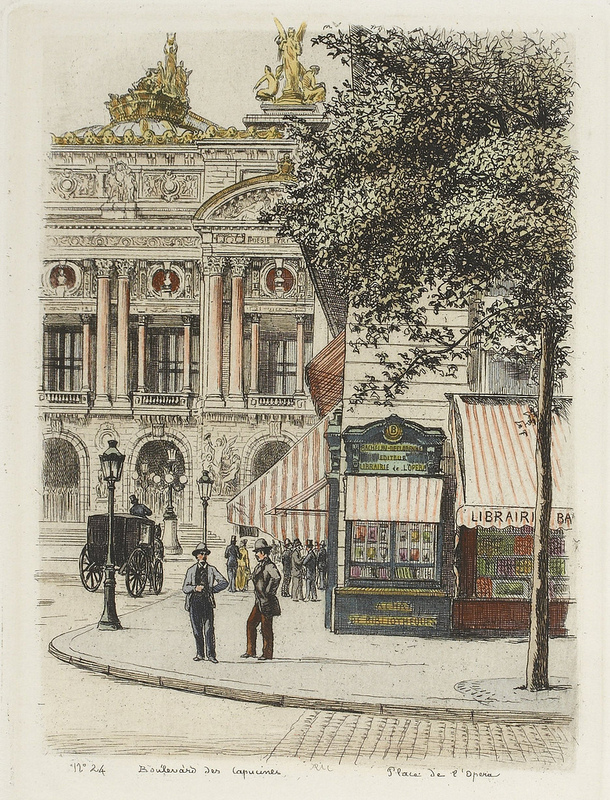

The political edifice proved fragile; and in 1870 it collapsed beyond all hope of reconstruction, but the Paris he built remained. In the broad new boulevards and avenues, the public buildings, the parks and squares, the networks of water mains and sewers, he left a permanent impression on the city. By 1870 his public works had given Paris its present appearance. The white domes of Sacré-Coeur did not yet top the hill of Montmartre nor did the Eiffel Tower break the low line of buildings on the Left Bank. Horses had not yet surrendered the streets to automobiles nor gas street lights given way to electric lights, but the tree-lined boulevards, the broad avenues, the many public parks and squares, the monumental buildings terminating long vistas were all there in 1870; and together with public markets, aqueducts and reservoirs, and great collector sewers created at the same time they have continued to serve Paris to this day.

Far beyond Paris, too, Napoleon III and his Prefect of the Seine, Georges Haussmann, left an indelible mark. For half a century and more their work profoundly influenced the city planning and civic architecture of the European world. . . .

The rebuilding of Paris was an immense and complicated operation, and its history is not a simple narrative of plans, demolitions, and building but a complex story of architecture and engineering, slum clearance and sanitation, emigration and urban growth, legal problems of expropriation and human problems of high rents and evictions, public finance and high politics, dedicated men and profiteers. It involved planning on an unprecedented scale -- parts of cities, even entire new cities like Versailles, Karlsruhe, or Saint-Petersburg, had been planned and built, but no one before had attempted to refashion an entire old city. It posed technical problems for which there were no ready solutions-no accurate map of Paris existed in 1850 and one had to be made, starting with triangulation of the whole city; no one knew how to measure underground sources of water supply; no one knew how to cut a trench through sandy soil big enough for a sewer that was a virtual underground river. The whole operation was constantly complicated by a growing population (the city's inhabitants nearly doubled in numbers in the 1850's and i86o's) that intensified difficulties of housing, provisioning, and sanitation.

The rebuilding of Paris was an immense and complicated operation, and its history is not a simple narrative of plans, demolitions, and building but a complex story of architecture and engineering, slum clearance and sanitation, emigration and urban growth, legal problems of expropriation and human problems of high rents and evictions, public finance and high politics, dedicated men and profiteers. It involved planning on an unprecedented scale -- parts of cities, even entire new cities like Versailles, Karlsruhe, or Saint-Petersburg, had been planned and built, but no one before had attempted to refashion an entire old city. It posed technical problems for which there were no ready solutions-no accurate map of Paris existed in 1850 and one had to be made, starting with triangulation of the whole city; no one knew how to measure underground sources of water supply; no one knew how to cut a trench through sandy soil big enough for a sewer that was a virtual underground river. The whole operation was constantly complicated by a growing population (the city's inhabitants nearly doubled in numbers in the 1850's and i86o's) that intensified difficulties of housing, provisioning, and sanitation.

Costs were enormous. In 1869 Haussmann estimated the expenditure on rebuilding the city since 1850 at 2,500,000,000 francs, about forty-four times the city's outlay on all expenses of government in 1851. An equivalent expenditure in New York City today, forty-four times the expenditures in the budget of 1956-57, would be $84,ooo,ooo,ooo. The city sought to raise the money from existing taxes (it levied no new ones), the resale of condemned property, subsidies from the national government (which always involved a struggle with the provincial majority in the Legislative Body), and public loans, but these means proved to be inadequate, and Haussmann resorted to less orthodox methods of financing that opened to political opponents of the Empire an avenue of attack upon the whole imperial regime and brought the rebuilding of Paris into national politics. In a democratic regime it would have become a political issue much earlier. The transformation of the city within two short decades probably would not have been accomplished in a state less authoritarian than the Second Empire.

The great rebuilding operation inevitably aroused opposition, and Haussmann, an aggressive and impatient man, did little to allay it. Provincial interests objected to lavish expenditures on the capital, and timid souls in Paris and out, recalling the Revolution of 1848, feared the growing proletarian population that public works attracted to the city. Conservative banking houses objected to spending they regarded as inflationary. Residents in particular quarters protested against real or fancied neglect of their neighborhoods. Condemnation of property for new boulevards and streets that cut across built-up areas disturbed established property rights and emotional attachments. Proprietors usually received generous indemnities, but thousands of tenants were forced by demolitions aid rising rents to leave familiar quarters in the old city and live in peripheral areas. For the hundreds who were dissatisfied, however, there were thousands who profited directly from the expenditures of the city (almost 20 per cent of the Parisian labor force was employed in the building trades at the height of the construction boom in the middle sixties) and thousands more who recognized the civic value of new streets, parks, sewers, and water supply. Orleanist and Republican opposition tried to exploit the discontent but without notable success until the latter 186o's, when they learned of Haussmann's unorthodox financial methods. Then the opposition drummed on "the fantastic accounts of Haussmann" as proof of the imperial regime's extravagance, incompetence, and irresponsibility, and momentarily they enjoyed success, forcing Haussmann from office in 1870 and slowing public works almost to a stop.